Emeritus professor tackles the thorny issue of his own university’s role in the failing Dutch nitrogen policy. By Marieke Enter, Resource – Wageningen University Magazine.

‘Wageningen doesn’t really have a good answer to the question of what should happen now’, Van der Ploeg claims. Photo Duncan de Fey.

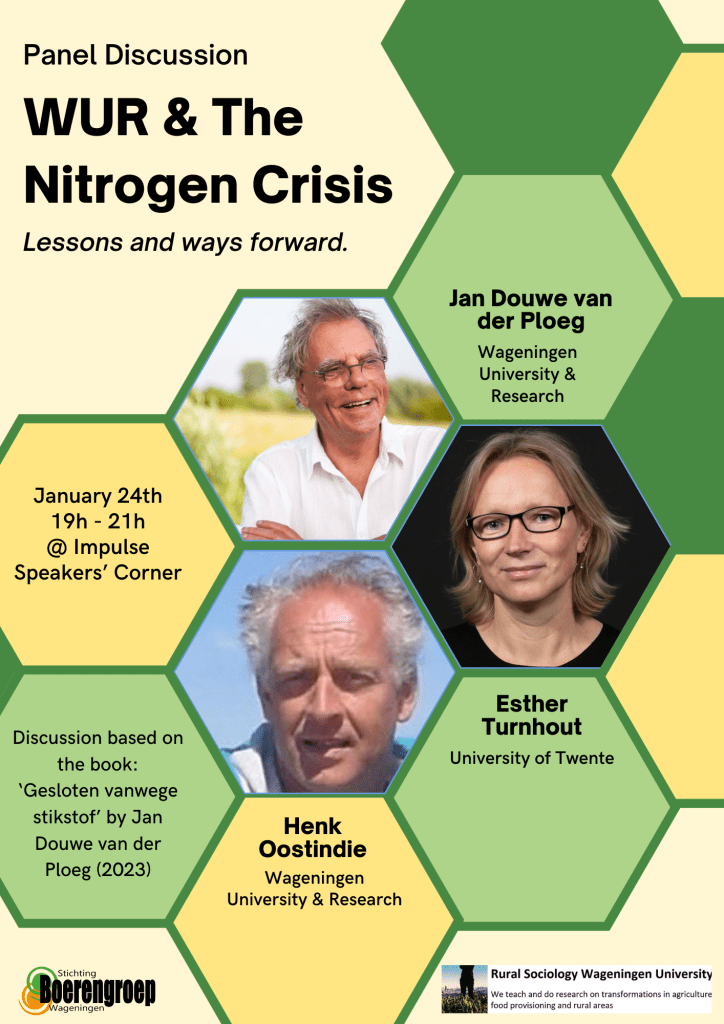

Emeritus professor Jan Douwe van der Ploeg has written a book that, according to the newspaper Friesch Dagblad, belongs on the new Minister of Agriculture’s bedside table and should be required reading for WUR’s Executive Board. It is an analysis of the failing Dutch nitrogen policy, in which he also tackles the thorny issue of his own university’s role. Resource asked him about the latter.

As professor of Rural Sociology, Van der Ploeg did research on modes of farming all around the world, with the contrast between ‘peasant farming’ and ‘entrepreneurial farming’ a recurring theme in his work. The former denotes farming based on circular resources provided by farmers themselves, including feed, soil, fertilizer and labour. The latter covers agriculture that depends heavily on inputs from elsewhere, such as concentrated feed, artificial fertilizers, machines and genetic material – making the agribusiness sector a major stakeholder. In his recent book Gesloten vanwege stikstof (Closed due to Nitrogen), he expands on the link between the almost unbridled faith in that kind of entrepreneurial agriculture and the Dutch nitrogen crisis, which he describes as ‘a problem that has been actively created over the past few decades’. According to him, it is not just agribusiness and the ministry of Agriculture that are to blame for the nitrogen problem. The Agricultural Sciences at Wageningen have played a key role in it too.

In what sense has Wageningen played such a crucial role?

‘Over the past six or seven decades, agriculture has fast grown into a massive agro-industrial complex. WUR was a strong driving force in that process. It was made clear to farmers that they had to say goodbye to their traditional practices and start thinking and working like entrepreneurs. The university totally identified itself with that process and went on to push it further, in close collaboration with the ministry of Agriculture and the agro-industry. There was too little attention to the downsides and the dangers of what was called “optimal agriculture”. And any interest in alternatives disappeared too, such was WUR’s confidence in the chosen path and in itself. And even today, WUR has a strange, ambivalent relationship with the process.’

In what way ambivalent?

‘On the one hand, the university boasts that the Netherlands has an incredibly efficient agricultural sector thanks to WUR’s expertise. But as soon as problems arise, such as the nitrogen crisis, suddenly it’s nothing to do with Wageningen – it’s all down to other factors. In reality, these problems were always looming; it’s just that WUR failed to recognize them sufficiently. There was never any proper critical forecasting. You should always ask yourself: where are the catches, how could things go wrong under the influence of all sorts of factors? If a university neglects to do that, you quite quickly find yourselves at the agro-industry’s beck and call. Not because you’ve been bribed or anything like that, but because you are operating within their frame of reference.’

Does the agro-industry’s frame of reference explain why there’s such a deadlock on the nitrogen issue?

‘Wageningen doesn’t really have a good answer to the question of what should happen now. That is painfully clear from the recent report WUR perspectives on agriculture, food and nature about dilemmas which rather makes my skin crawl: should we take animal welfare into consideration? Should the Netherlands feed the world? Those ceased to be dilemmas a long time ago: everyone knows which direction we should go in. Even worse to my mind is the fact that the report’s conclusion boils down to a single proposal: ‘we need a societal and a political debate.’ That makes my blood boil. Is WUR really calling for a debate straight after the carefully conducted dialogue on the agricultural agreement was a total flop? I think it’s a show of incompetence that WUR can’t come up with anything better than that.’

And yet that WUR report came in for criticism from a number of agribusiness organizations, which sent an open letter to WUR President Sjoukje Heimovaara saying that WUR should focus on doing research and not be ‘for’ or ‘against’ anything.

‘That underscores just how seriously entangled the interests have become. As soon as the university even slightly questions the status quo, it’s: Have you taken leave of your senses? Get back in line and get on with business as usual!’

But Heimovaara didn’t toe the line. Could that be a sign of a wind of change blowing through Wageningen?

‘Compared with Aalt Dijkhuizen’s bulldog behaviour and Louise Fresco’s stubbornness, you could call this a commendable step forward, yes. But the question is whether it’s enough. Clinging to the theory of optimal agriculture, while it obviously flies in the face of reality, was a remarkable mistake that WUR made. And that calls for some serious soul-searching by the university: how could we have let ourselves get swept along by a theory when the empirical data has long been clear: hey, guys, that’s not how it works, in reality it’s much more complex.’

Do you have an explanation for the dynamics of that?

‘In recent decades there have always been people, departments and networks that realized that at the very least, additional research was needed to avoid mishaps. Only there was proportionally little or no funding that that. And that’s still the case, and it’s partly because of where the funding comes from. It’s outrageous that co-financing from the business world is always required. We are thereby letting the business world have a big say in where the “relevance horizon” lies, to use a term from knowledge theory. What lies outside that is dubbed irrelevant – so there is no funding for or interest in it. But the painful fact is that innovation often takes place precisely beyond that horizon, in the margins.’

So students and staff who are concerned about the close ties between WUR and agribusiness have a point?

‘Of course! They’re absolutely right, in my view. You see, I’m part of the generation that joined forces in the Boerengroep (farmers’ group)* Looking back on that now, supporters and critics will agree that it achieved a lot. Let’s hope that a new wave of that kind rolls through the university. The word sometimes gets a bit overused, but Wageningen needs a change of culture.’ (* The Boerengroep is a still existent Wageningen student organization known for its critical take on agriculture, which aims to bring agricultural theory and practice closer together, in collaboration with farmers.)

In what way?

‘There’s a contradiction inherent in the demand that WUR, as a merger of the former DLO agricultural research institutes and the former university departments, should present a united front to the rest of the world. Because in the market the DLO institutes operate in, knowledge is a commodity. Being right is crucial: why would anyone hire you if you admit that you are sometimes wrong? For them it is essential to say: we are right, we’ve always been right, and we guarantee that we’ll be right in future. Compare that with the university, where doubt is the basis of science – constantly asking and investigating: is that really right? It is extremely important that we get a good internal debate going, and that we look for new theoretical perspectives.’

Is that also why you applaud more competition for WUR?

‘WUR’s hegemony is in marked contrast to other European countries. They all have several agricultural universities and faculties – that is so even in a small country like Belgium. As a result, in debates you are sure to get a variety of starting points and critical views of one other. The Netherlands has just the one agricultural science institute, which carefully guards its monopoly: Wageningen. It’s true that Leiden, Amsterdam, Groningen and Nijmegen are now cautiously venturing into the agricultural domain. I think it would be a good development if it becomes more pluriform. Hopefully, that would stimulate the Wageningen supertanker to change course.’

The book Gesloten vanwege stikstof describes how a socio-technical regime developed in the Netherlands – made up of interlocking and mutually reinforcing institutes, laws, technologies, assumptions, routines, interests and identities – which has resulted in the nitrogen problem and is now powerless and unwilling to solve the problem. That may sound like a shady conspiracy, but Van der Ploeg emphasizes in his introduction that there is much more to it than naked self-interest and clandestine agreements. ‘It’s more a case of an (often unintentional) web of sub-processes and interests. This book is an attempt to map the source, the course, the bends and the power of that current.’