75th Anniversary: 50) Research Agenda: “Do-It-Yourself Development”

Years ago, on a sunny day in Spring 2005, I drove down a bumpy road with no signage to a village in the mountains of Kurdistan. It was the last leg of a long journey. Yet, the bumpy village road was not the most difficult part of the journey. These were the numerous military checkpoints on the highway into the region at that time. For a “tourist,” the common designation for a foreigner in the area, getting past the checkpoints was a challenge.

Some 100 kilometers previously, in the city of Diyarbakir, I had become acquainted with a few of the inhabitants of this village. In teahouses in the city, we had had long conversations about the evacuation of their villages and the struggle they were waging to be able to return. They told me they had cleared the roads in and around the village, established their own shuttle service, and, after a short period of sleeping in tents, some had begun to build new houses where piles of stones marked their old homes.

It was a mountain village with a composite character. There were clusters of houses on the slopes where people used to earn an income growing vegetables and tending animals, mostly sheep. The village had been evacuated in 1994 by the Turkish Armed Forces and paramilitary in their struggle against the armed insurgency of the Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK. It was just one of the approximately 3,000 villages evacuated and burned by the military as they believed that the PKK drew membership, logistical support, and intelligence from the rural population.

Although the forced migration of Kurdish villagers had become a subject of study, most of the research done focused on the city and the various forms of social exclusion with which the displaced villagers were confronted. In the cities in the western part of Turkey, the forced migrants were regarded as a “threatening other,” politically and culturally polluting the urban environment.

My own interest was in the struggle of these forced migrants for the right of “the right to return” and the way they practiced this right with their feet. They refused to sign-up to the fantasy “return” projects of the state, which aimed at a redesign of the countryside by developing a new settlement structure to facilitate outside control, and never got beyond the stage of planning and the construction of a handful of model projects. They did not sign the documents that would bargain permission to go back to their villages in return for exoneration of the state responsibility for burning down their houses by blaming “terrorism”, instead. Facing a variety of obstacles – ranging from intimidation by the (para)military through the absence of previously available public services, such as education, healthcare, and water and electricity supplies to the neoliberal turn in agricultural policies – a steady trickle of people began to return.

At the time, I referred to this as a “counter-track” in “return” to village. A “track” because it involved self-organized resource mobilization and distinct movements of people back to the old rural settlements and to contrast this messy process with the administrative organization and coordination that characterizes an officially sanctioned return scheme. A “counter” track since it ran against the reconstruction approach of the state and its plans to develop a compact and concentrated settlement structure. Interestingly, the “return” evolved into a multifaceted process in which people part returned, or rather developed a living pattern in which rural and urban living intermeshed. They became both villagers and urbanite, both working the land and running businesses in the city. The “return” turned out not to be about migrating from the city to the village but about developing a relationship between the two.

After the early 2000s, the years in which I did my Ph.D. research, I studied further situations and practices in Kurdistan in which people were striving to take their fate and future into their own hands. I developed a research interest in individual and collective practices through which people, as Marshall Berman once described it, “change the world that is changing them.” Among others, this “them” referred to the complex or multiple identity of the villager-city dwellers as outsider peasants and Kurds. And it was a combination of the market and state’s identity politics that made “peasants” and “Kurds” vulnerable identities.

The world that was changing them as peasants involved the implementation of neoliberal policies in the early 2000s by the government of Turkey, facilitated and enforced by international organizations like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and European Union. This included a major state withdrawal from its previous support of agriculture that resulted in a squeeze on the smallholder (“family farm”) population. Price liberalization resulted not only in lower returns and increased income insecurity, the policy established the “the peasantry” as the “other” of modern agriculture– like the poor urban migrant was the “urban other” and the Kurd the “cultural other” – identities to be dissolved.

Against expectation and received wisdom, however, the new neoliberal economics did not result in a major reduction of the number of small farms. Instead, by developing counter-trajectories, strategic evading the requirements of the neoliberal policies, families have managed to hold on to their land and continue farming. They did this by diversifying income generation strategies – among others through an increased engagement in labour relations outside the farm – in the local town, nearest or distant city. This diversification of income sources contributed to a living structure in which the rural and urban intermeshed.

The world that was changing this “them” as Kurds was related to a politics of cultural dispossession. Among others, a modernization of agriculture had been employed for the production of a Turkish administrative and cultural imprint on the population in the region. Large infrastructure programs, such as the dam and irrigation projects executed by the Southeast Anatolia Project (GAP), served as a vehicle for the extension of state control in rural areas and conversion of Kurdish peasants into Turkish farmers. Under the protection of a state of emergency, this modernization policy had developed a colonial economic system in which the role of the region in the country became that of a supplier of resources.

In the 2010s, as part of a Kurdish movement that brimmed of self-confidence, several initiatives flourished in the wider region that aimed to interrupt the state’s identity politics, the political economy of resource extraction, and demographic engineering through a strengthening of community economies, diversification of production, the development of nested markets and ideas of fair price. This occurred in a context of lively debates about new forms of politics that centered around the idea of active citizenship and a politics beyond the (nation-)state.

Do-It-Yourself Development thus emerged as a concept through which I was able to understand all these initiatives and debates as creative ways to develop alternatives “for the world that is changing them”. Just as the idea of “counter-tracks” had helped me to make visible the messy process of self-organized return – one that was more significant than the official return projects of the state, which were bombastic in design, yet did not have much meaning in the life of people – Do-It-Yourself Development enabled me to identify and group an alternative approach to development and the ideas that guide its manifold expressions.

Theoretically, Do-It-Yourself Development provides for an analysis that allows me to move beyond the imagination constraints of the dominant, homogenizing political economy, that requires us to conceive the world we live in from the perspective of capital and state and the dependence and submission they produce. Do-It-Yourself Development creates a crucial inversion: by adopting the viewpoint of daily life and social struggle, vigorous forms of self-organization, self-creation, and self-administration become visible, not just as reactive responses but as innovative and inspiring initiatives – as future making. This makes Do-It-Yourself Development a sociology of possibilities, an approach to the study how “the other” claims and reclaims better worlds in the here and now.

Joost Jongerden is associate professor at the Rural Sociology Group. His publications are available at https://wur.academia.edu/JoostJongerden

The joy of fermentation

written by Noortje Giesbers based on her MSc thesis

Fermentation is a practice that has been around for ages, with the earliest archaeological finds dating back to 13.000 BC (Liu et al., 2018). It is a natural process provided by the microorganisms present on the food, they ferment the food through their metabolism (Katz, 2012). In the past, but also in the present does fermentation of food contribute to food security all over the world by enabling people to preserve food (Hesseltine & Wang, 1980; Quave & Pieroni, 2014). Many well-known and daily products incorporate a fermentation process, such as bread and beer. But also coffee, yoghurt, chocolate, wine, cheese and soy sauce, to name a few.

In the recent years, I got interested in fermentation, in the process and making my own foods. I shared this interest with a growing number of people. It got me my thesis topic: Motivations for home-fermentation in the Netherlands. From January till August 2021 and with the help of five experts and ten home-fermenters, I conducted this study. My fermentation knowledge and food technology background, as well as Satters’ hierarchy of food needs and the social practice theory helped me to understand the workings at play in the fermentation trend.

Fermentation might seem old-fashioned, but is more intertwined with modern day life than one would expect: it draws attention to craft food-making, taste, identity, and to traditional ecological knowledge put into practice to sustain microbiological ecologies (Flachs & Orkin, 2019). As Tamang et al. (2020) note: “The nutritional and cultural importance of these ancient foods continue in the present era.”. Lee & Kim (2013) state that fermented food is deeply rooted in the ways of life, the local environment, eating habits and deeply related to the produce, in different regions. So, when studying fermented foods, one is studying the close relationships between people, organisms, and food, since the practice of fermentation involves both biological and cultural phenomena, which simultaneously progress (Steinkraus, 1996). This can be showcased by kimchi, which is a part of culture and identity for Koreans, or fermenting fish is for the islanders of the Faroe Islands (Jang, Chung, Yang, Kim, & Kwon, 2015; Svanberg, 2015; Tamang et al., 2020). Yet, by some Dutch consumers, it has also become a part of their food identity, creating ways to lower their food waste, increasing flavour profiles, increasing their gut health.

Fermentation fits well with a more sustainable way of living, with a hedonistic approach to food and a healthy lifestyle, all often reasons to ferment for Dutch consumers. One of the experts noticed three groups of fermenters: those who ferment for the experimentation and flavour; for the health benefits; or to relieve health problems. A fourth group was mentioned by another expert: those who ferment to be self-sufficient. This motivation can stem from the distrust in the global food system and/or the lower ecological impact of growing your own foods. Each home-fermenter included in this study could be linked to one or more groups, following their personal reasons for home-fermenting.

The main motivations for home-fermentations are established, but how is this practice recreated in society? The social practice theory states that for a social practice to be reproduced, one needs three things (Hargreaves, 2011; Reckwitz, 2002; Shove, Pantzar, & Watson, 2012; Vermeer, 2018):

- The actual “Things” that compose social practices;

- Meanings, that provide the practice with direction; and

- Competence, to carry out the practices.

I propose the idea that by making ferments, sharing them, sharing knowledge (competence), starters (“things”) and ideas (meanings), one socially reproduces the practice of home-fermentation, spreading the home-fermentation practice and inspiring more people to home-ferment. By fermenting home-fermenters have enjoyable foods, but also encounter a lot of joy. Statements included enjoying working with foods and sharing the outcomes, as well as the practice. The feeling of accomplishment and being proud of making something yourself, like with other hobbies, is true for home-fermentation as well, as seen by this and other studies (Click & Ridberg, 2010; Murray & O’Neill, 2015; Sofo, Galluzzi, & Zito, 2021; Yarbrough, 2017). Home-fermenters are proud of their ferments and proudly share them too. Which also brings joy to those that they share it with, as acknowledged by an expert.

This liking of sharing ferments, how it can positively influence relationships was also noticed by one of the experts. It was found that fermentation can (re-)connect people, just like foods and other hobbies can do. By having a hobby to talk about and ferments and starter cultures to share, home-fermenters made new friends, reconnected to old ones, or strengthened their current friendships.

It is not uncommon, as sharing food with others has been observed not only to be enjoyed, but can also express creativity and care (Clair, Hocking, Bunrayong, Vittayakorn, & Rattakorn, 2005). Similarly, home-fermenters would prepare a certain ferment for guests later that week. Others share their starters, recipes, and tips & tricks; teach others and make it a fun activity. You could say that next to sharing the actual product of their practices, home-fermenters also share some of the “things” and competence.

To conclude, next to adding to health, sustainability and specific personal feelings, fermentation brings joy, above all else. So dear reader, if you would like to know more, find the full thesis via the link below. If you would like a starter or learn, I am happy to share and teach!

Cheers, Noortje

References

Clair, V. W.-S., Hocking, C., Bunrayong, W., Vittayakorn, S., & Rattakorn, P. (2005). Older New Zealand Women Doing the Work of Christmas: A Recipe for Identity Formation. The Sociological Review, 53(2), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00517.x

Click, M. A., & Ridberg, R. (2010). Saving food: Food preservation as alternative food activism. Environmental Communication, 4(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2010.500461

Flachs, A., & Orkin, J. D. (2019). Fermentation and the ethnobiology of microbial entanglement. Ethnobiology Letters, 10(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.14237/ebl.10.1.2019.1481

Hargreaves, T. (2011). Practice-ing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to pro-environmental behaviour change. Journal of Consumer Culture, 11(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540510390500

Hesseltine, C. W., & Wang, H. L. (1980). The Importance of Traditional Fermented Foods. BioScience, 30(6), 402–404. https://doi.org/10.2307/1308003

Jang, D. J., Chung, K. R., Yang, H. J., Kim, K. S., & Kwon, D. Y. (2015). Discussion on the origin of kimchi, representative of Korean unique fermented vegetables. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 2(3), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.08.005

Katz, S. E. (2012). The Art Of Fermentation (M. Goodman & L. Jorstad, Eds.). White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Lee, J. O., & Kim, J. Y. (2013). Development of cultural context indicator of fermented food. International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology, 5(4), 45–52.

Liu, L., Wang, J., Rosenberg, D., Zhao, H., Lengyel, G., & Nadel, D. (2018). Fermented beverage and food storage in 13,000 y-old stone mortars at Raqefet Cave, Israel: Investigating Natufian ritual feasting. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 21(May), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.08.008

Murray, D. W., & O’Neill, M. A. (2015). Home brewing and serious leisure: Exploring the motivation to engage and the resultant satisfaction derived through participation. World Leisure Journal, 57(4), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2015.1075899

Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2014). Fermented foods for food security and food sovereignty in the Balkans: A case study of the gorani people of Northeastern Albania. Journal of Ethnobiology, 34(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-34.1.28

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a Theory of Social Practices. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Sofo, A., Galluzzi, A., & Zito, F. (2021). A Modest Suggestion: Baking Using Sourdough – a Sustainable, Slow-Paced, Traditional and Beneficial Remedy against Stress during the Covid-19 Lockdown. Human Ecology, 49(1), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-021-00219-y

Svanberg, I. (2015). Ræstur fiskur: Air-dried fermented fish the Faroese way. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0064-9

Tamang, J. P., Cotter, P. D., Endo, A., Han, N. S., Kort, R., Liu, S. Q., … Hutkins, R. (2020). Fermented foods in a global age: East meets West. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(1), 184–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12520

Vermeer, A. (2018). Enacting social practices of food: performing food and nutrition security (Wageningen University). Retrieved from https://edepot.wur.nl/450868

Yarbrough, E. (2017). Kombucha Culture: An ethnographic approach to understanding the practice of home-brew kombucha in San Marcos, Texas (Texs State University). Retrieved from https://digital.library.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/6756/YarbroughElizabeth.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

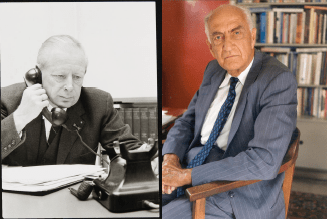

75th Anniversary: 49) Hofstee has left his mark on Wageningen studies on extension communication

Cees Leeuwis*

Prof. Anne van den Ban is generally regarded as the founding father of the Wageningen communication sciences. He was appointed as Professor of extension communication (‘Voorlichtingskunde’) in 1964, which became the cradle for a rich and influential array of academic endavours at the intersection between communication, innovation and change in the sphere of health, environment and agriculture. These activities have continued until today and now take place across several chairgroups and sections at Wageningen University.

While Prof. Van den Ban certainly deserves a lot of credit for developing the new discipline and building an internationally recognized group, it is important to acknowledge the contribution of Prof. E.W. Hofstee in getting Van den Ban started. Hofstee was promotor of Van den Ban’s 1963 PhD dissertation on the communication of new farm practices in the Netherlands, and he no doubt inspired Van den Ban in choosing his topic. In fact, already in 1953 Hofstee wrote about the importance of studying ‘sociological aspects of agricultural extension’ in the first (!) ‘Bulletin’ that was published by his group (Hofstee, 1953). He was also in touch with the public extension services that had been established by the Ministry of Agriculture a few decades earlier, and gave lectures to Ministry staff on the significance of group-based agricultural extension approaches (e.g. Hofstee, 1960). Reading these early works by Hofstee made me -as one of the successors of Van den Ban- realize how much we still owe to Hofstee today.

In essence, Hofstee criticizes the then prevailing extension services and practices for assuming that farmers take decisions according to an individualistic economic rationale. He points to the importance of social, collective and cultural dynamics in shaping what farmers do or do not, and also to the importance of social differentiation and regional ‘farming styles’ in explaining farmers’ economic activity. In order to be effective, extension organisations and professionals should -according to Hofstee- understand the importance of such ‘sociological aspects’ and anticipate these in their work (Hofstee, 1953). This implies that extension workers should look at extension and knowledge transfer as an inherently social process rather than as a series of communicative ‘tricks’ and also be reflective about their own social positions (Hofstee, 1960) The concern with the ‘effectivess of extension’ (or better: the lack of it) demonstrates Hofstee’s commitment to the post second world war modernisation project and his own normativity in this regard. Despite his sensitivity for social and normative issues, he continued to talk in terms of ‘good, progressive’ and ‘bad, backward’ farmers (Hofstee, 1953), thereby (re)producing the paternalistic connotations of the Dutch word for extension communication: ‘Voorlichting’. This term literally means something like ‘holding a light in front of someone to lead the way’ assuming apparently that people are ‘in the dark’ and need to be ‘enlightened’ by those with scientific training.

While today’s studies on communication, innovation and change have arguably left this ‘enlightenment’ and ‘deficit’ thinking behind, we also see traces of Hofstee coming back in our current work. We still criticize simplistic individualist conceptualizations of change, as is reflected in today’ attention for ‘social-technical configurations’, ‘system transformation’ and ‘responsible innovation and scaling’. Similarly, Wageningen trained communication scientists are known for their interactional and socio-political conceptualization of both professional and everyday communication and meaning making, and for their interest in the social challenges to facilitating dialogue among different interpretative communities. These sociological perspectives on communication and change have now spread to other Universities in the Netherlands and elsewhere. The continued prevalence of sociological connotations is not surprising if one considers that most of Van den Ban’s successors indeed had a sociological training as well. Clearly, that is not accidental but part and parcel of Hofstee’s legacy.

*Cees Leeuwis is Personal Professor at the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation group, Section Communication, Philosophy and Technology

References

Hofstee .E.W. (1953) , Sociologische aspecten van de landbouwvoorlichting. Bulletin 1, Afdeling Sociale en Economische Geografie, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen.

Hofstee .E.W. (1960) Inleidende opmerkingen over de voorlichting: Groepsbenadering in de voorlichting. Voordracht gehouden op de Tuinbouwdagen 1960. Mededelingen van de Directeur van de Tuinbouw, 23, 10, pp 621-624

Van den Ban, A.W. (1963) Boer en landbouwvoorlichting: De communicatie van nieuwe landbouwmethoden. Pudoc, Wageningen.

Start Teaching them Young: Connecting Children to the Local Food Chain (thesis/internship)

This thesis/internship assignment will investigate the opportunities of educational programs for school pupils on the topic of local food and farming. It will draw from a literature review and work on a local case of the Tiny Restaurant, located in the municipality of Laarbeek in the Dutch province of North Brabant.

The Tiny Restaurant is a grassroots, non-profit initiative aiming to bring producers and consumers together. It takes a form of a pop-up (mobile) restaurant that provides a meeting place for (in)formal exchange of knowledge. One of the projects of the Tiny Restaurant is educating children about the food chain through an experiential culinary program. The Tiny Restaurant wants to ensure its educational approach fits the schools’ learning goals and contributes to the ultimate purpose of creating a long-term connection between farmers and consumers. The goal of this assignment is to evaluate the current approach and advise on how the educational program can be improved. The following questions form a starting point:

- How can educational programs enhance awareness about local food production?

- How does the theme of local food chains fit schools’ curricula and learning goals?

- What is the optimal balance of head (conveying information), heart (shaping attitudes) and hands (learning by doing) in these educational programs?

Depending on the student’s preference, the assignment can be more academic (e.g. using a literature review to learn about education for sustainability) or more applied (e.g. working on the Tiny Restaurant educational program, together with local farmers and teachers). The vacancy is part of a broader Science Shop project which, together with local stakeholders, explores possibilities of connecting producers to local inhabitants in Laarbeek. Starting dates are flexible, with results delivered by the end of May the latest. For more information contact Lucie Sovová lucie.sovova@wur.nl