I recently traveled to France for a short walking spring break. In the north eastern part of the country I visited the Alsace region. I stayed in the area left of the city of Colmar near the village called Munster (well known for its ‘smelly’ cheese). Although the break was a way of resetting my brain, I couldn’t stop myself from observing some interesting things.

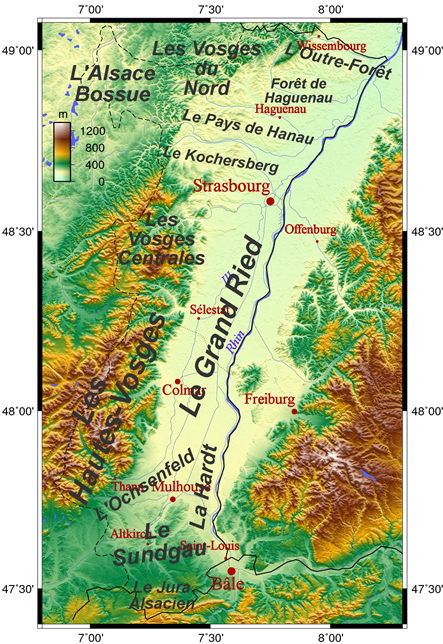

The Alsace region

Although the Alsace is French, the area is characterized by many German influences. Not surprisingly because the area changed hands many times. The area has a strong regional identity which expresses itself physically, culturally and historically (architecture (timber framed houses), landscape, dialect, kitchen and regional products). The stork can be seen as the region’s main symbol and almost disappeared in the 1970’s. The region put a lot of effort in bringing ba ck the bird (by starting breeding programs) and now storks can be found on roofs of houses and public buildings everywhere. All these things are characteristic to the Alsace region.

ck the bird (by starting breeding programs) and now storks can be found on roofs of houses and public buildings everywhere. All these things are characteristic to the Alsace region.

Wine walks

An important and unnoticeable regional product is wine (Vin d’Alsace) like Riesling, Gewürztraminer and Pinot Blanc. Since Roman times the Alsace has a strong tradition in growing grapes and over time has developed as a centre of viticulture. The area has an excellent terroir: good weather, climate, fertile soils and sunny slopes. Part of the rocky hilltops every small piece of the area is cultivated for growing grapes. This viticulture can bee seen as the (historical) backbone of this region into which over time whole sets of other activities got interwoven: visiting historical villages, local products / food, touristic walks etc. Central to this all is the wine and the attractiveness of the region. On my break I explored one of these really nice walks near the village of Kaysersberg. The walk started in climbing a woody and rocky hill and lead through the village of Riquewihr and via extensive vineyards back to were we started. In the vineyards information panels were placed to give information growing techniques, pruning, different varieties and the winemaking process. During the walk we stopped at several wine farmers / cooperatives for some refreshments and wine tasting.

These wine walks are an interesting way of using regional identity and products for regional development. The combination of activities, services and goods attracts tourists, strengthens the regional economy and contributes to the vitality and livability of this specific region. I got the impression the Alsace region is very succesful in this!